I am a historian with a focus on China and its place in the modern world, with a particular interest in how our perceptions of the past – and of non-Western cultures in especially – stand up to what the historical record reveals.

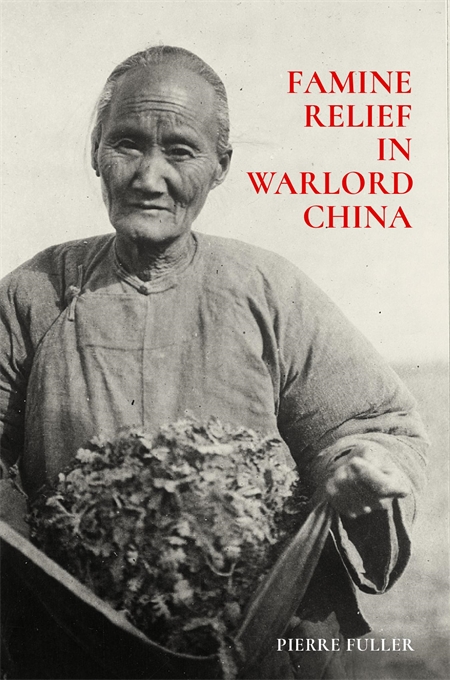

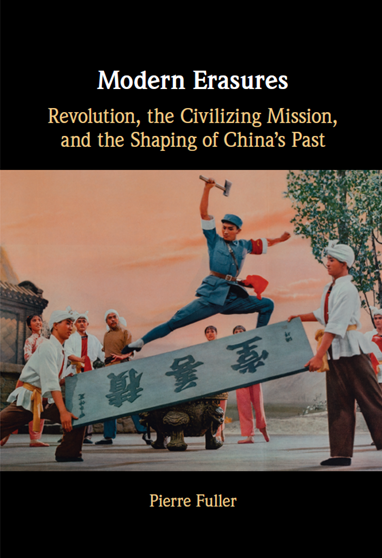

My writing has investigated little-understood disaster relief systems in late 19th and early 20th-century China to show how they undermine the universalist claims and Western-centric narratives provided by the field of humanitarian history. More recently, I have examined the surprising kinship between how revolutionary movements, such as Maoism, and European colonial and missionary projects described and intervened in the lives of rural peoples in East Asia. I am currently looking into early ethnographic writing by French and English explorers in 18th and 19th-century Tasmania and broader Australasia, exploring parallels with the development of social scientific study of Chinese in the 19th and 20th centuries.